The U.S. commercial real estate (CRE) sector is under growing strain, and the stress isn’t confined to landlords. Regional banks, which hold a disproportionate share of CRE loans, are also in the crosshairs.

The Scale of the Problem

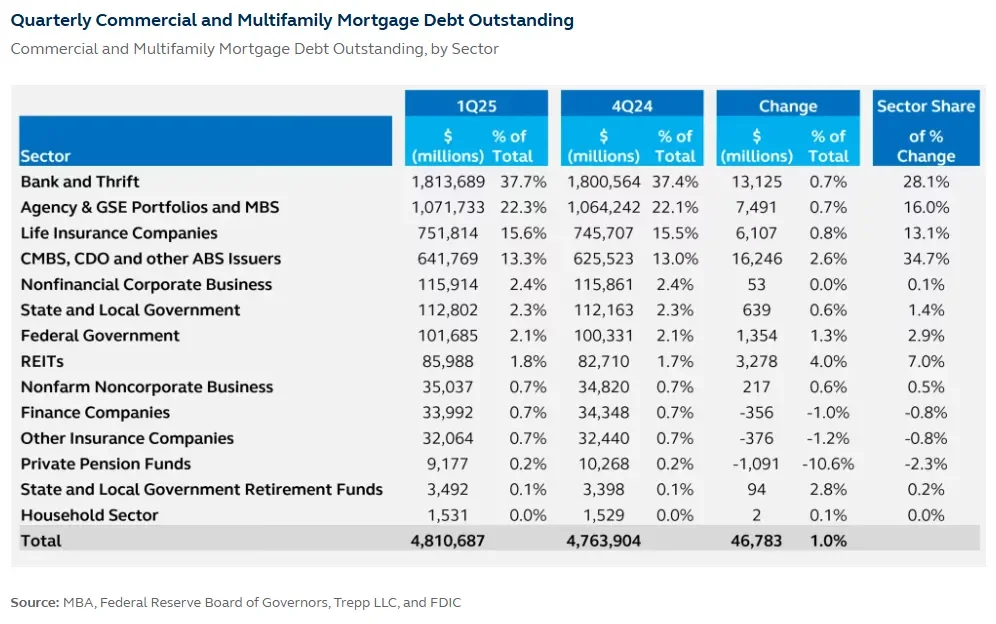

CRE debt outstanding sits near $6 trillion, with banks holding about 40% of that exposure. Regional and community banks account for the bulk, especially in loans tied to office buildings and retail properties.

Office vacancies in major U.S. cities hover around 20%—double pre-pandemic levels. In New York and San Francisco, some submarkets are closer to 30%. Valuations have fallen accordingly, with some properties trading at 40–50% discounts compared to peak pricing.

The Refinancing Cliff

The timing is especially painful. Roughly $1.2 trillion of CRE debt is set to mature between now and 2027. Many loans were originated in an era of 3–4% rates. Refinancing today often means 7%+ borrowing costs, coupled with lower appraisals.

That combination—higher debt service plus lower collateral value—creates what analysts call a refinancing gap. For some borrowers, it’s simply not feasible to roll debt forward without injecting fresh equity.

Why Banks Are Exposed

Large money-center banks diversified away from CRE after the financial crisis. Regional banks did not. For many, CRE makes up 30–40% of their total loan books, compared to single digits for the biggest banks.

This creates an asymmetric risk: a wave of write-downs may not destabilize Wall Street, but it could squeeze regional lenders, limit credit availability, and ripple through local economies.

Early Warning Signs

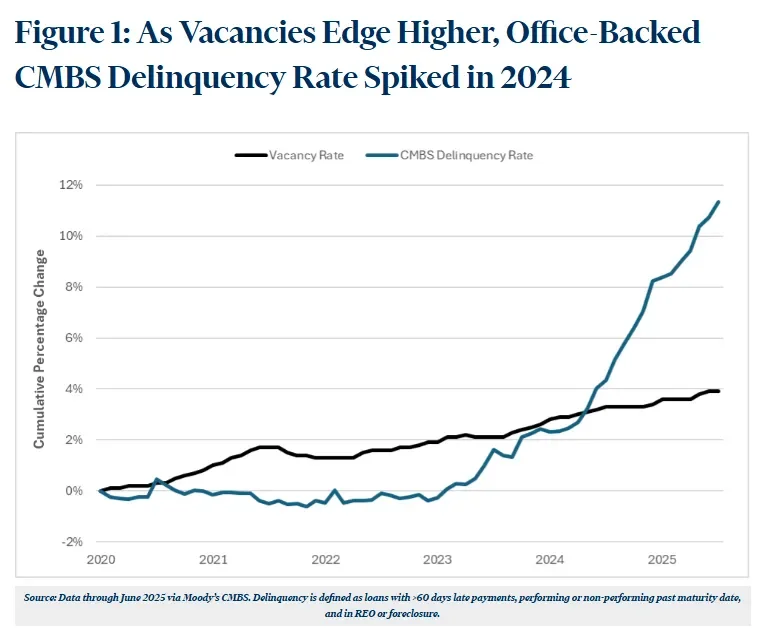

We’re already seeing stress surface:

Office loan delinquency rates hit 7% in August 2025, the highest since 2012. The FDIC’s Q2 report flagged CRE as a “top supervisory priority.” Fitch Ratings has warned that some regional banks could see earnings compression or capital strain if CRE values fall further.

Broader Implications

Why does this matter beyond landlords and lenders?

Credit tightening: If regional banks pull back, small businesses—heavily reliant on local lenders—face tougher borrowing conditions.

Local economies: Cities depend on property tax revenue. Falling CRE valuations mean budget shortfalls, service cuts, or higher taxes.

Financial stability: A localized problem can metastasize if confidence in regional banks erodes, echoing the failures we saw in early 2023.

Looking Ahead

Much hinges on interest rate policy and labor market trends. If the Fed cuts rates meaningfully, some refinancing pressure could ease. If office demand stabilizes or repurposing gains traction, valuations may find a floor.

But the structural shift—remote work reducing demand for office space—is unlikely to reverse. That suggests this isn’t just a cyclical downturn. It’s a reset in how commercial property is valued and financed.

In other words, CRE distress may be the slow-moving story that keeps regional banks under pressure for years to come.