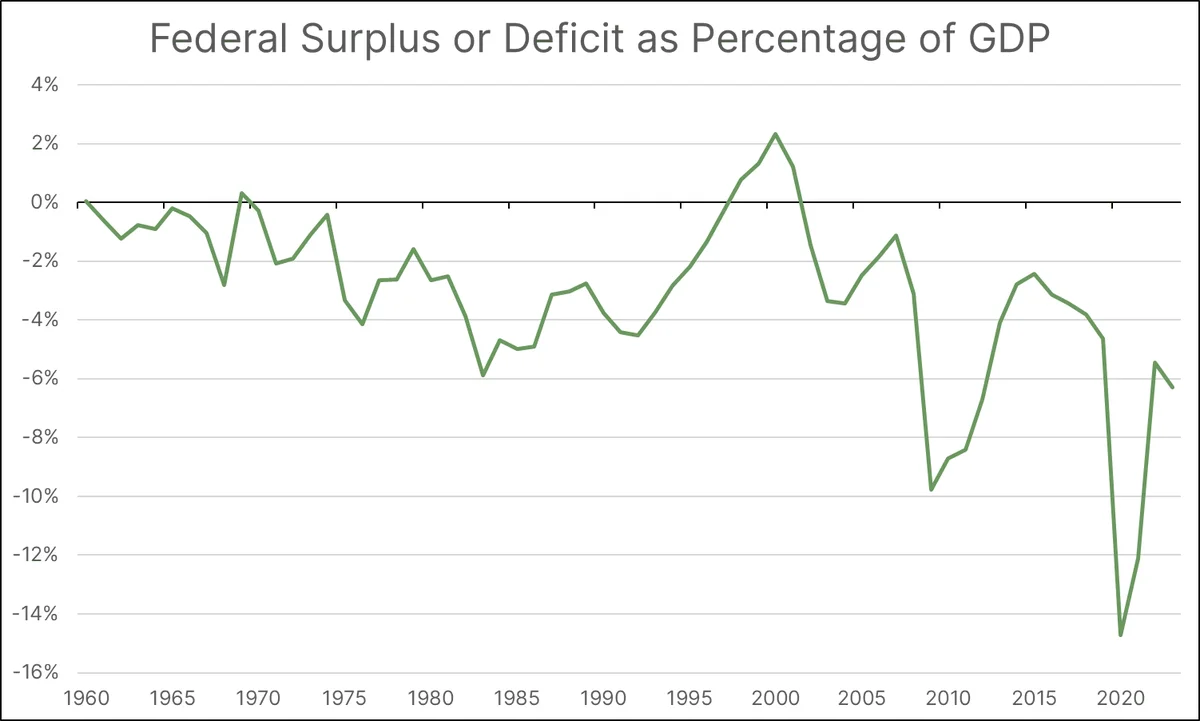

Over the past couple of months, there has been considerable discussion about the deficit and potential solutions. We’ve taken a deep dive into the data to explore how a balanced budget could be achieved, and what we found may surprise you.

The Three Components

There are three important components to consider when evaluating the budget deficit: spending, revenue, and growth in gross domestic product (GDP). The first two—spending and revenue—are fairly self-explanatory, so we’ll focus on GDP growth.

When measuring the deficit as a percentage of GDP, it’s important to account for changes in GDP, as this can offset the deficit. For example, if we run an annual deficit equal to 3% of GDP, but GDP also grows by 3% in the same year, the annual change in government debt as a percentage of GDP will be zero. Keep this in mind, as we’ll revisit this component later.

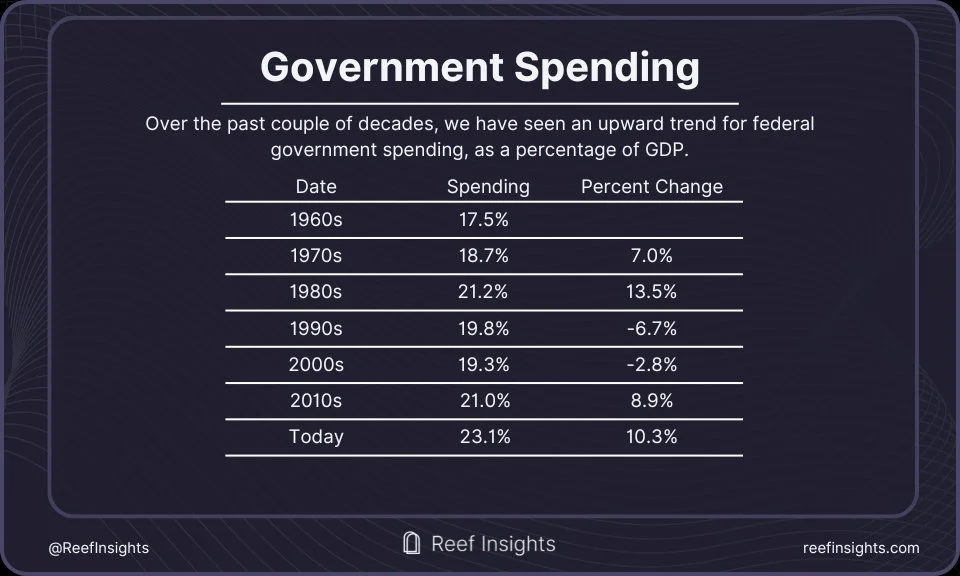

Government Spending Trends

Since the 1960s, government spending has generally trended upward. In the 1990s, President Clinton was able to reduce spending. This trend continued under President Bush in the 2000s; however, revenue declined during this period, offsetting the potential deficit reductions. Today, government spending remains elevated compared with historical norms.

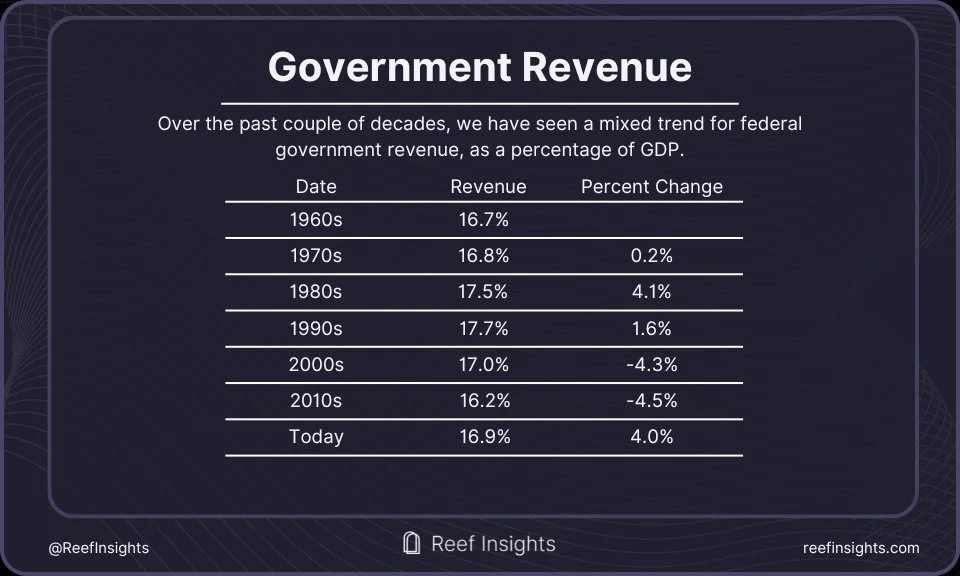

Government Revenue Trends

Since the 1960s, government revenue has followed a mixed trend. In the 1990s, revenue peaked under President Clinton, and, combined with reduced spending, this produced a budget surplus—a result not seen since. Under President Bush in the 2000s and President Trump in the 2010s, government revenue declined. Today, revenue remains largely in line with historical norms.

The GDP Growth Problem

Since the 1960s, GDP growth has slowed after peaking in the 1980s. This trend is not unique to the United States; developed countries around the world have experienced similar slowdowns in GDP growth.

The importance of this trend cannot be overstated, as slower growth reduces the deficit a government can run without increasing its debt-to-GDP ratio.

In summary, spending has risen, revenue has remained flat, and GDP growth has slowed.

Understanding the True Deficit

Before moving on, let’s look at a formula that can showcase what we’ll call the “True Deficit.”

If we were running a deficit equal to 3% of GDP, but we saw GDP growth of 3%, the formula may look something like this:

In this scenario, government debt, as a percentage of GDP, does not grow or shrink.

Let’s plug in today’s figures to see where we stand:

Today, the True Deficit is -2.1%. In other words, government debt is growing, as a percentage of GDP.

Solving Through Spending Cuts Alone

So, how might we go about reducing the True Deficit to zero? Keep in mind, if the True Deficit is zero, this means that debt is not growing or shrinking, which doesn’t necessarily solve our problem, but it gets us trending in the right direction.

If you wanted to solve this problem by only adjusting spending, we would need to reduce spending by 9.0%.

Before examining what this would look like, we need to explain the difference between discretionary and nondiscretionary spending. Discretionary spending requires annual approval and allocation by Congress, whereas nondiscretionary spending is funded based on existing laws. In other words, discretionary spending can be altered without adjusting current legislation and nondiscretionary spending cannot.

In 2024, discretionary spending only accounted for 27% of total spending. Additionally, roughly half of total discretionary spending goes toward defense.

If you wanted to achieve a True Deficit solely by a discretionary spending reduction, you would need to reduce discretionary spending by 33.3%, and if you didn’t want to impact defense spending, you would need to reduce it by 66.6%.

It’s safe to say that this would never be the solution, so you would need to pass legislation to alter nondiscretionary spending.

Solving Through Revenue Increases Alone

If you wanted to solve this problem by only adjusting revenue, we would need to increase revenue by 12.4%. This would raise revenue to 18.9% of GDP—well above the highest decade-long average on record, which was 17.7% in the 1990s under President Clinton.

Again, it’s safe to say this would never be the solution, so let’s consider something possible—albeit unlikely.

A Return to 1980s Levels

If we returned to where levels were in the 1980s with today’s GDP growth, our formula would look like this:

This result means that we would have a True Surplus, which would decrease the debt-to-GDP ratio over time.

This plan would require an 8.4% reduction in spending and a 3.8% increase in revenue—no small change, but a return to levels we have seen before.

Three Critical Considerations

Before concluding, we want to discuss three things: GDP Growth, Current Policy, and Adjustment Considerations.

GDP Growth

You may have noticed that GDP growth plays a role in the adjustments that need to be made. Past generations greatly benefited from GDP growth of 8–9%. A good proxy for how this benefited them is as follows:

If you increase your debt by 6% each year but receive annual pay raises of 8% of your salary, your debt, as a percentage of your income, is declining. Now imagine the same scenario, but with raises of only 4%. In that case, your debt, as a percentage of your income, is growing.

Because GDP growth has slowed, we need to rethink government spending and revenue generation. This change fundamentally alters how we can approach budgeting.

There has been speculation that AI could boost GDP growth in the future. However, until such growth materializes, we must address the certain problem: a growing deficit. It is not prudent to pencil in GDP growth rates based on assumptions that may never come to fruition. Instead, it is more practical to make adjustments today, which can later be altered if that growth does occur.

Current Policy

Due to the passage of the One Bill Beautiful Bill, which cemented the tax cuts passed in Trump’s first term, increasing revenue does not appear to be a strategy this administration will pursue. Moreover, the spending cuts associated with the bill did not offset the lost revenue, meaning the deficit is expected to rise.

In other words, as things stand, this administration is making the problem worse—contrary to campaign trail promises.

Setting politics aside, the last serious attempt to address this issue came under the Clinton administration. In the 1990s, a combination of reduced spending and a slight increase in revenue produced a budget surplus.

Looking ahead, voters should consider candidates who recognize that this is not a single-pronged issue. If we are to seriously right size the deficit, we must address both spending and revenue, not just one component.

A Note on Tariffs

Despite claims to the contrary, tariffs are paid by domestic importers, and these costs are passed on to consumers through higher prices. In essence, tariffs function as a tax, thereby increasing revenue. However, one significant drawback—among many—is that this form of taxation disproportionately affects low-income Americans.

On average, higher-income individuals save more, while lower-income individuals save less and spend a larger share of their income on goods. As a result, the poorest Americans feel the effects of tariffs more acutely than the wealthy.

This is known as a regressive tax, which places a heavier burden on lower-income households. While there are other examples of regressive taxes, many Americans agree that this is not an ideal tax structure.

This is not to say that taxation of lower-income groups cannot be part of a budget-balancing strategy, but it is to emphasize that tariff revenue is inherently regressive. And that’s without even touching on the many other drawbacks of tariffs—a conversation for another time.

Adjustment Considerations

Spending reductions and revenue increases do not occur in a vacuum; both will negatively impact GDP growth. This is why we chose to examine a solution that allows for some room to absorb a slight decline in GDP growth.

There is no solution to this problem that comes without drawbacks—something Americans and politicians must accept. Unfortunately, neither party appears willing to make such adjustments, which is not surprising.

Politicians are elected on promises about the future, but regardless of party, these promises often fail to materialize. There may be no perfect solution to this challenge, but it could be that addressing this political reality is the first step toward solving the fiscal problem outlined in this piece.