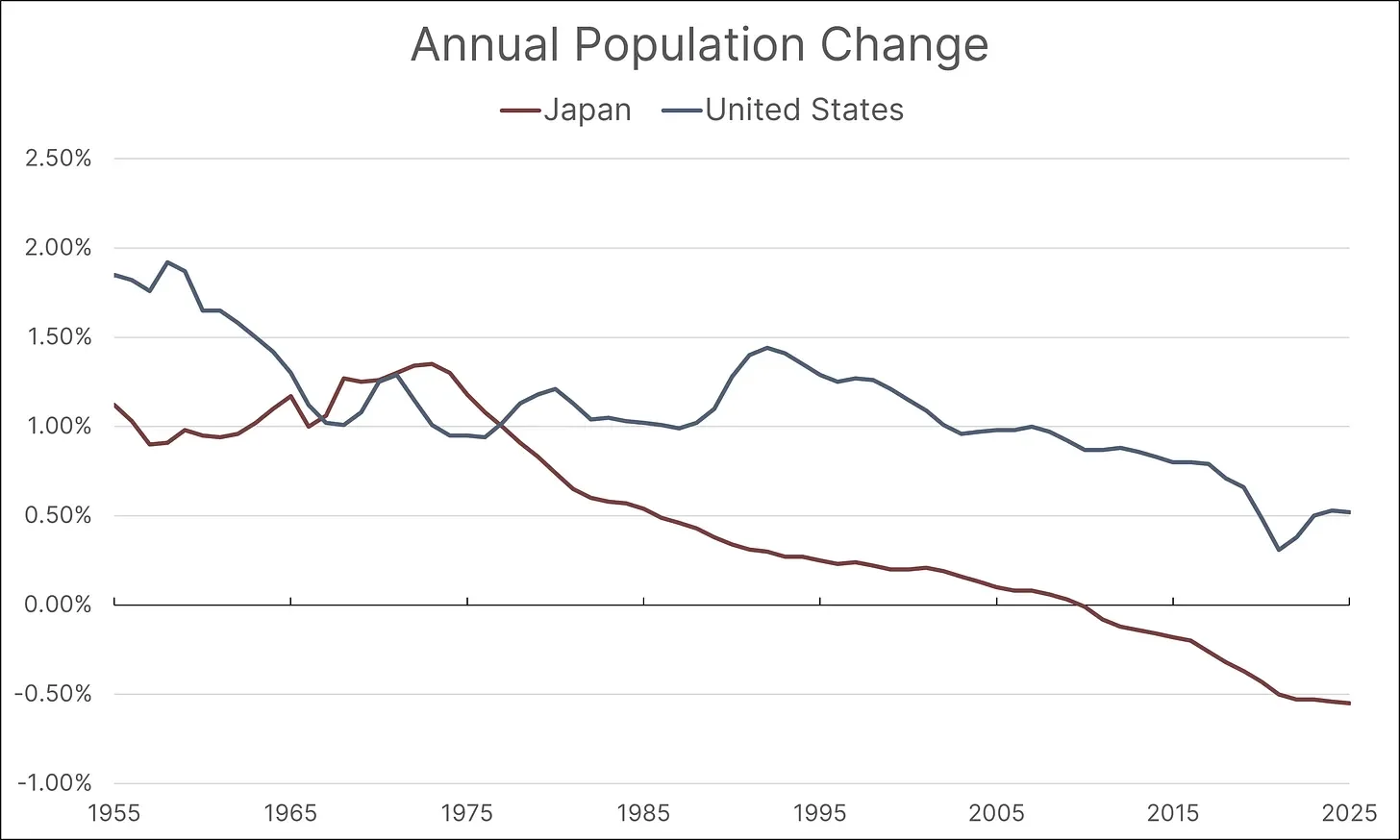

In 2024, two people died for every baby born in Japan.

At first glance, this might seem irrelevant to the United States. However, we argue that Japan’s situation highlights why government debt could become a serious concern in the future.

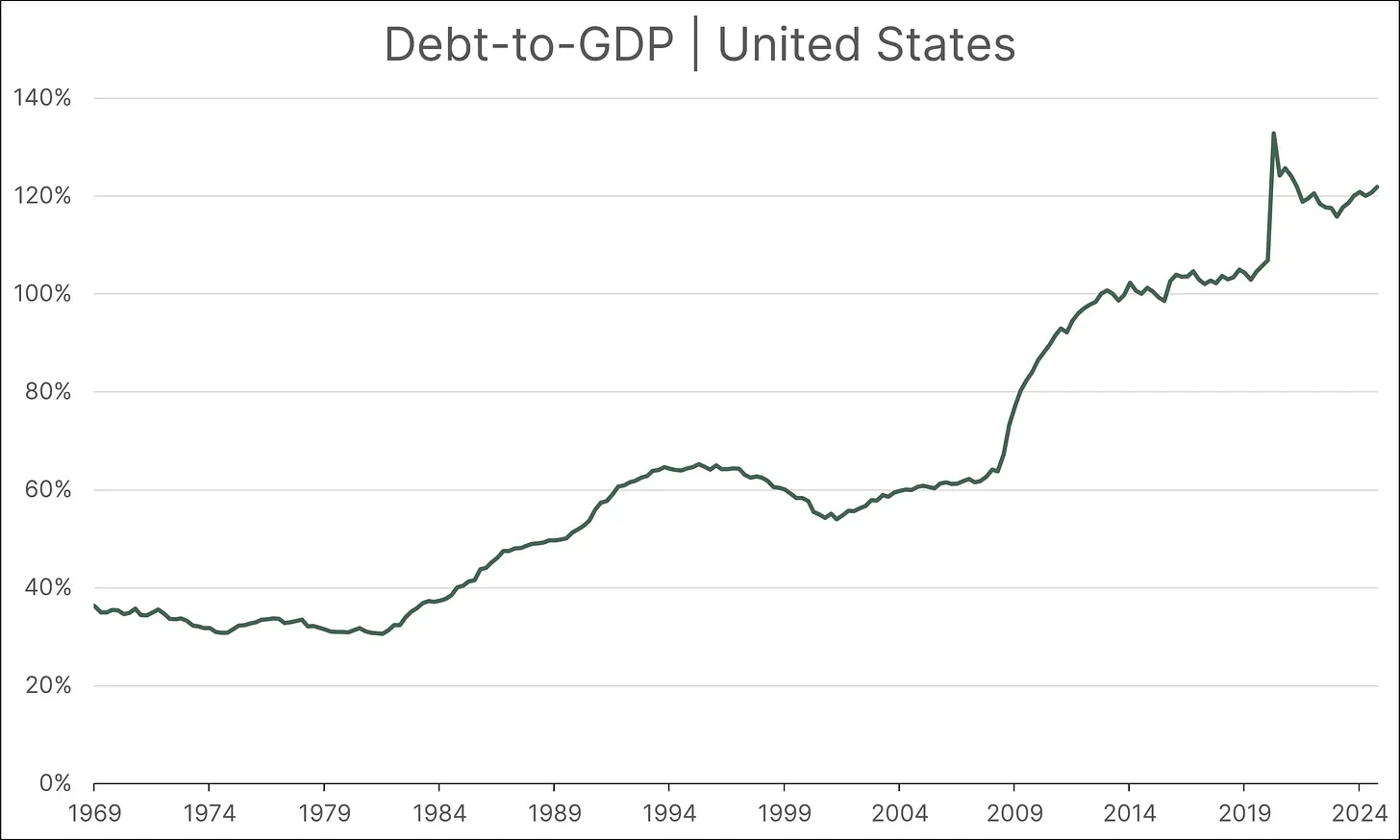

The debt-to-GDP metric is relatively simple: divide a nation’s government debt by its gross domestic product. But this ratio rests on an assumption that’s been quietly eroding over the past few decades.

What happens when a country’s fertility rate falls below replacement level? The U.S. isn’t currently on this path—largely thanks to immigration. Without it, we too might face similar economic headwinds tied to population decline.

As debates about the federal deficit continue, it’s important to recognize a largely overlooked factor: population decline. If the United States were to significantly restrict immigration and/or if fertility rates continue to fall, we could find ourselves facing challenges similar to those looming for Japan.

The Connection Between Fertility and Debt

Initially, these two issues—fertility and debt—may seem unrelated. By the end of this write-up, though, their connection will be clear.

Since 2010, Japan’s population has been shrinking due to two primary factors: low fertility rates and restrictive immigration policies.

According to the World Bank, Japan’s fertility rate stood at 1.2 in 2023. For context, replacement-level fertility is 2.1. Without enough immigration to offset this gap, Japan’s population has been declining—a trend that’s persisted for the past 15 years.

Can Immigration Solve Japan’s Demographic Problem?

Possibly. But to date, Japan’s immigration policies have emphasized cultural homogeneity and have remained relatively restrictive. If Japan wants to avoid a full-blown population collapse, it may need to rethink this approach.

How Does the U.S. Compare?

According to the World Bank, the U.S. fertility rate was 1.6 in 2023—also below replacement level. However, the U.S. has maintained more open immigration policies, which has allowed its population to continue growing despite low fertility.

The Link to Government Debt

So what does this have to do with government debt?

Great question. Let’s revisit the debt-to-GDP equation—specifically the GDP side, which reflects the total value of goods and services produced in a country. In the short term, small population changes may not have a noticeable effect on GDP. But over the long term, major demographic shifts can have meaningful economic consequences.

A Domestic Example: Detroit

To illustrate this, consider a U.S. microcosm: the Rust Belt, which includes states like Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. These regions show us what happens when population decline takes hold.

Detroit, Michigan, for example, has seen its population drop from over one million in 1990 to just 633,000 in 2023—a 38% decline over 33 years. The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis only provides GDP data for Detroit starting in 2001, but this still offers useful insight.

Between 2001 and 2023, Detroit’s real GDP (adjusted for inflation) grew by 17.4%.

That doesn’t sound too bad—until you compare it with national real GDP, which grew by 65% over the same period. Detroit significantly underperformed relative to the broader U.S. economy.

You might say, “Well, of course Detroit lagged. It’s an auto-manufacturing city, and globalization hit it hard.”

You’d be right. That’s part of the difficulty in finding domestic examples of population decline—most U.S. cities are growing. Those that are shrinking often have unique causes for doing so.

Interestingly, for the first time since 1990, Detroit’s population actually increased—albeit marginally—between 2022 and 2023. A contributing factor may be the city’s shift away from its heavy reliance on auto manufacturing toward other industries like healthcare, financial services, and technology.

What This Tells Us

What does this tell us? GDP growth often slows when a dominant industry fades, leading to population decline as people leave in search of better opportunities.

Now, let’s return to Japan. It is effectively bypassing the stage where a specific industry fades, and heading straight into a nationwide population decline.

The danger of slower GDP growth is that governments may need to reduce spending or take on more debt. And if the proportion of working-age citizens—the primary contributors to tax revenue—shrinks, this becomes even harder.

As a cautionary example, consider Detroit’s 2013 bankruptcy—the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history. While multiple factors were involved, a declining population was undeniably one of them.

Japan’s Debt Crisis

In 2023, Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio reached 250%—the highest in the world. If the country can’t reverse its demographic trajectory through increased fertility or more open immigration policies, it could face prolonged periods of weak GDP growth and stagnating tax revenue.

This, in turn, may make it increasingly difficult to pay off existing debt without resorting to additional borrowing.

In 2022, a report from the United Nations estimated that Japan’s total population could decline to 104.9 million by 2050, and possibly fall as low as 87 million by 2060. In 2023, Japan’s population stood at 124.5 million, meaning those forecasts would represent declines of 15.7% and 30.1%, respectively.

Implications for the United States

The United States currently maintains a debt-to-GDP ratio around 120%—high by historical standards, but far below Japan’s 250%. However, the trajectory is concerning. As the chart above shows, U.S. debt-to-GDP has been climbing steadily since the early 2000s, with sharp increases following the Great Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The key difference between the U.S. and Japan lies in demographics. While both countries have fertility rates below replacement level, the U.S. has benefited from more open immigration policies that have continued to fuel population growth and economic expansion.

But what if that changes?

If the United States were to significantly restrict immigration—as has been proposed by various political factions—while fertility rates remain low, the country could find itself on a path similar to Japan’s. A shrinking working-age population would mean:

- Lower tax revenues to service existing debt

- Slower GDP growth, making the debt-to-GDP ratio harder to manage

- Increased pressure on entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare

- Potential for a debt crisis if markets lose confidence in the government’s ability to repay

Conclusion

Japan’s demographic and fiscal crisis offers a sobering preview of what can happen when a country’s population begins to shrink while its debt continues to grow. The connection between fertility rates, immigration policy, and government debt is not immediately obvious, but it becomes clear when we consider the long-term dynamics of economic growth.

For the United States, the lesson is straightforward: maintaining a growing population—whether through higher fertility rates, immigration, or both—is not just a social issue but an economic imperative. Without it, even the world’s largest economy could find itself struggling under the weight of its debt, just as Japan does today.

The debt-to-GDP ratio is not just a number. It’s a reflection of whether a country can generate enough economic activity to support its financial obligations. And when the denominator—GDP—stops growing because the population is shrinking, that ratio can quickly become unsustainable.

As policymakers debate immigration reform and fiscal policy, they would be wise to keep Japan’s example in mind. The future of America’s fiscal health may depend not just on spending and taxation, but on ensuring that there are enough people to drive the economy forward.