Over the past few decades, concerns about the national debt have been steadily rising—and data suggests those concerns are warranted.

Let’s take a closer look at whether the debt is truly a problem, and how the government might go about addressing it.

Historical Perspective

The debt-to-GDP ratio rose sharply during World War II due to massive wartime spending. While this spending helped the Allies win the war, it caused the national debt to skyrocket.

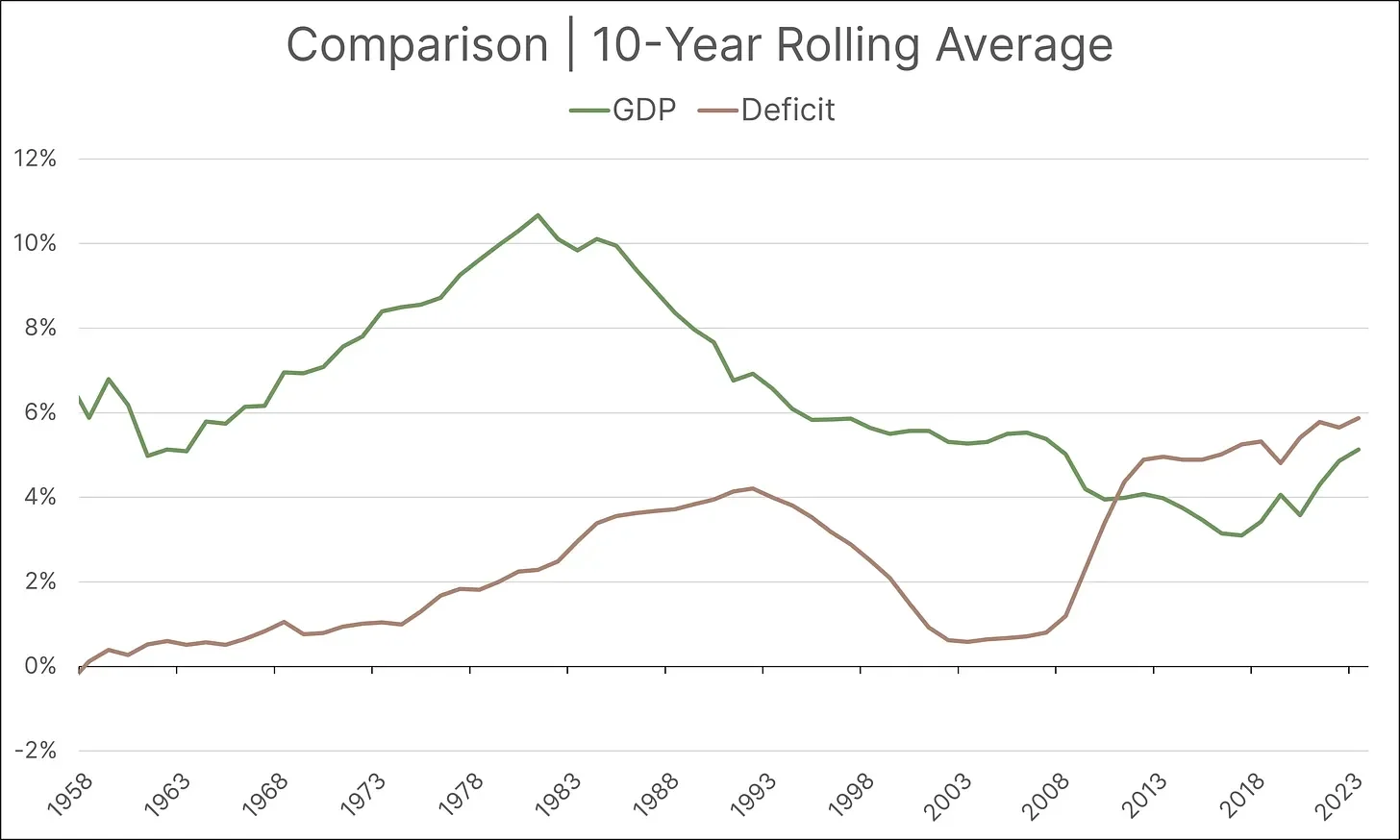

Over the following decades, the ratio declined—not because the government ran a surplus, but because GDP growth consistently outpaced deficit spending.

In other words, if a country grows its GDP at a faster rate than it increases its debt (as a share of GDP), the debt-to-GDP ratio will decline.

This framework makes sense, since government revenues typically scale with GDP.

Current Picture

The chart below illustrates how GDP growth has slowed while deficit spending has increased. In fact, over the past decade, deficit spending has consistently exceeded GDP growth—causing the debt-to-GDP ratio to climb.

If this continues unchecked, the ratio will keep rising. This may be problematic—not for the reasons often cited by pundits—but due to deeper structural issues.

Debt Dynamics

There are three primary ways the U.S. government can reduce its debt-to-GDP ratio. Let’s examine each, and explore their implications.

1. Reduce Spending & Increase Revenue

The government could cut spending and raise taxes. Depending on what areas are targeted, this could significantly affect millions of Americans.

For example, the most recent budget bill includes cuts to SNAP, Medicaid, and other programs that support lower-income households.

On the tax side, rather than increasing revenue, the bill proposes extending the tax cuts implemented during Trump’s first term.

To truly reduce the deficit, a two-pronged approach—cutting spending and increasing taxes—is needed. Currently, only one side of the equation is being considered, while the other (extending tax cuts) actually counters the intended fiscal tightening.

In fact, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that if the proposed budget bill is passed, it will increase the deficit by $2.4 trillion over the next decade—despite claims to the contrary from the administration.

2. Grow GDP Faster Than the Deficit

The second option is to grow GDP at a rate that outpaces deficit spending. This method is mostly outside the government’s direct control.

While government investment can help boost GDP, we haven’t seen consistent economic growth strong enough to offset current levels of deficit spending—pandemic rebound aside.

So while this path is theoretically viable, it’s unlikely under current conditions.

3. Repurchase Debt

The final option is debt repurchase.

The government could buy back its own debt—either by repurchasing existing securities on the open market or by purchasing new issuances directly.

You might ask: Why doesn’t the government do this already?

There are several reasons, but the primary concern is inflation. When the government repurchases Treasuries, it essentially swaps bonds for cash. That cash can re-enter the economy, increasing demand and potentially driving up prices.

Despite popular rhetoric, the Federal Reserve doesn’t literally “print money.” Rather, when it buys Treasuries, it’s creating bank reserves to remove those securities from circulation—affecting interest rates and liquidity, not flooding the streets with dollars.

Still, if these repurchases cause inflation, the bond market could suffer. The U.S. will never technically default—it can always create money to meet obligations—but the true risk to investors and households is inflation, not insolvency.

The Four Levers

As economist Stephanie Kelton explains in The Deficit Myth, the real constraint on government spending is inflation, not borrowing capacity.

Investor Ray Dalio, in The Changing World Order, outlines four levers that governments can pull to reduce debt burdens:

- Austerity (spending less)

- Debt default or restructuring

- Wealth redistribution (higher taxes)

- Printing money and devaluing the currency

Since default is off the table for the U.S., that leaves us with: cutting spending, raising taxes, or printing money.

The Road Ahead

As the debt-to-GDP ratio continues to climb, it will likely become an increasingly urgent policy issue. For now, however, the U.S. government doesn’t appear eager to make the necessary adjustments.