We’ve spent the past few days poring over state-level data to determine how home prices or mortgage rates would need to adjust to return to the 10-year average for affordability.

What we found is, quite frankly, shocking—and it challenges much of the prevailing narrative.

Assumptions

We used state-level median household income data from the U.S. Census Bureau. However, the most recent available data only goes through 2023. To estimate figures for 2024, we referenced a report from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, which found that current-dollar personal income increased at an annual rate of 4.6% in the fourth quarter of 2024. Based on this, we assumed a 5% year-over-year increase in median household income from 2023 to 2024.

When calculating mortgage payments for each period, we assumed a 20% down payment by the borrower.

Please note that the data does not account for property taxes or homeowners insurance, both of which are components of a typical mortgage payment. In other words, if property taxes or insurance costs have grown faster than median household income, the required adjustments to home valuations or mortgage rates would be larger. Conversely, if those costs have grown more slowly, the adjustments would be smaller.

Calculations

For each state, we used median household income data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the prevailing mortgage rate for each period from Freddie Mac, and the median home sales price from Redfin. Using these inputs, we calculated the percentage of median household income required to service the mortgage—a figure we’ll refer to as MHIR (Mortgage-to-Household-Income Ratio).

After determining MHIR for each period, we calculated the 10-year average. From there, we ran two scenarios:

- We calculated what the median home sales price would need to be for the current MHIR to align with the 10-year average MHIR.

- We calculated what the mortgage rate would need to be for the current MHIR to match the 10-year average.

In other words, these revisions to home values and mortgage rates are mutually exclusive—either adjustment alone would bring the current MHIR back in line with the 10-year average.

Findings

Across all states, the average downward revision to the median home sales price was 29.3%. In practical terms, this means a $500,000 home would need to be priced at $353,500 to align with the 10-year average MHIR. Similarly, the average revised mortgage rate came out to 3.68%.

In every state, either a reduction in home values or a decline in mortgage rates was necessary to bring the current MHIR back in line with its 10-year average. The largest adjustment was observed in Connecticut, where home values would need to fall by 37.3% or mortgage rates would need to drop to 2.72%. The smallest adjustment occurred in Louisiana, requiring a 20.9% reduction in home values or a decline in mortgage rates to 4.62%.

The five states requiring the largest revisions were Connecticut, New Jersey, New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York. The five states needing the smallest revisions were Louisiana, Alaska, Texas, Wyoming, and Kansas.

Mortgage Spreads

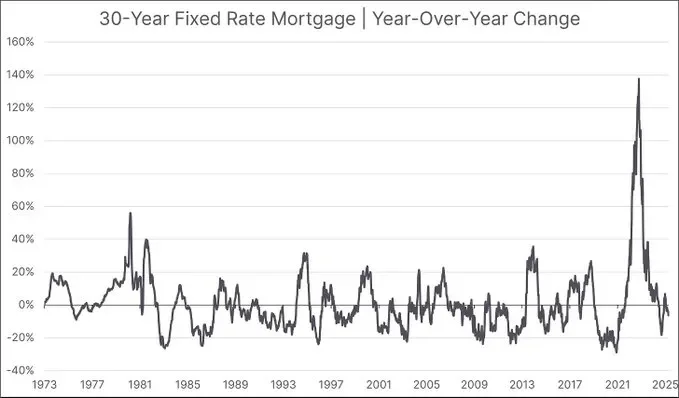

As shown in the previous section, mortgage rates—regardless of state—would need to decline significantly to return to historical affordability norms. In a recent paper, we highlighted the seismic shift that took place in 2022, when mortgage rates increased 137.6% year over year.

Looking back to 1973, this was by far the largest annual increase on record. The second-largest occurred in 1980, when rates rose by 56% year over year. Without repeating the entire analysis, the long-standing trend of declining mortgage rates and rising home values has partially reversed. As of May 15, 2025, the Freddie Mac Primary Mortgage Market Survey reports a mortgage rate of 6.81%. However, home prices have yet to adjust meaningfully in response to this sharp increase in rates.

We’ll address why home values have remained elevated later in the paper, but first, we want to explore mortgage rate dynamics—and why a return to prior affordability levels may be unlikely under current conditions.

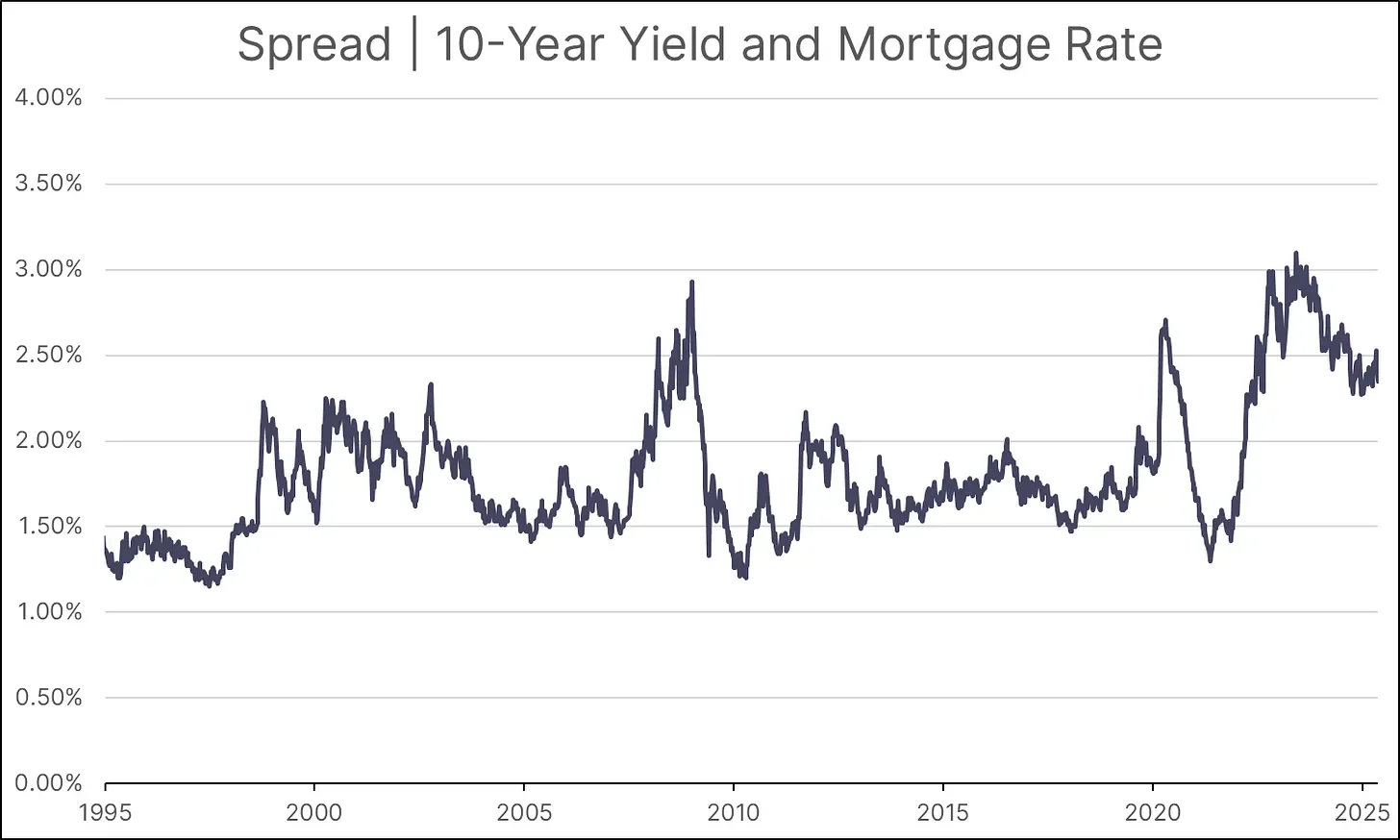

Mortgage rates are highly correlated with the 10-Year U.S. Treasury yield, with a correlation coefficient near 1. However, the spread between the two can vary significantly depending on broader economic conditions. As of May 15, 2025, the spread between the 10-Year U.S. Treasury yield and mortgage rates stood at 2.35 percentage points. The 10-year average spread is 2.03 percentage points, suggesting that mortgage rates could decline by approximately 32 basis points if the spread were to normalize.

However, this modest decline would not bring any state close to the mortgage rate levels needed to return to the 10-year average MHIR. For affordability to improve meaningfully, the 10-Year Treasury yield would need to fall to around 2%.

Given a range of factors—tariff uncertainty, inflation expectations, and continued deficit spending, to name a few—it’s difficult to argue that the 10-Year Treasury yield will experience a significant decline in 2025.

The Supply Myth

The commonly held belief is that the U.S. suffers from a housing shortage, but that belief is likely misguided.

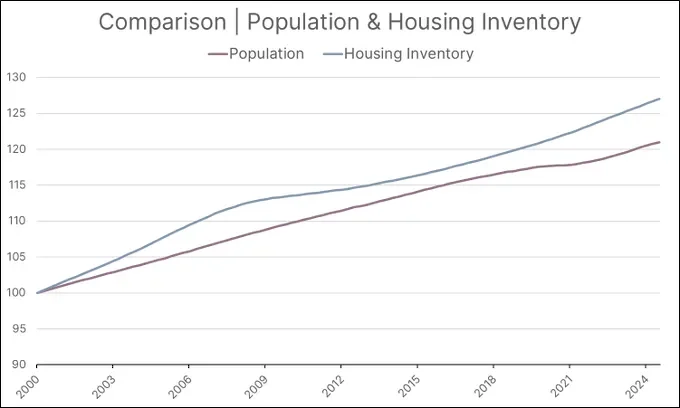

In the chart above, we analyzed the growth for population and total housing inventory since 2000, and we found that total housing inventory grew by 27%, which is markedly higher than the 21% growth in population.

New research from the University of Kansas finds that most of the nation’s markets have ample housing in total, but nearly all lack enough units affordable to very low-income households.

Kirk McClure and Alex Schwartz co-wrote a study last year that was published in the journal Housing Policy Debate.

They examined U.S. Census Bureau data from 2000 to 2020 to compare the number of households formed to the number of housing units added to determine if there were more households needing homes than units available.

The researchers found only four of the nation’s 381 metropolitan areas experienced a housing shortage in the study time frame, as did only 19 of the country’s 526 “micropolitan” areas—those with 10,000-50,000 residents.

“There is a commonly held belief that the United States has a shortage of housing. This can be found in the popular and academic literature and from the housing industry,” McClure said. “But the data shows that the majority of American markets have adequate supplies of housing available. Unfortunately, not enough of it is affordable, especially for low-income and very low-income families and individuals.”

“Our nation’s affordability problems result more from low incomes confronting high housing prices rather than from housing shortages,” McClure said. “This condition suggests that we cannot build our way to housing affordability. We need to address price levels and income levels to help low-income households afford the housing that already exists, rather than increasing the supply in the hope that prices will subside.”

New Home Inventory

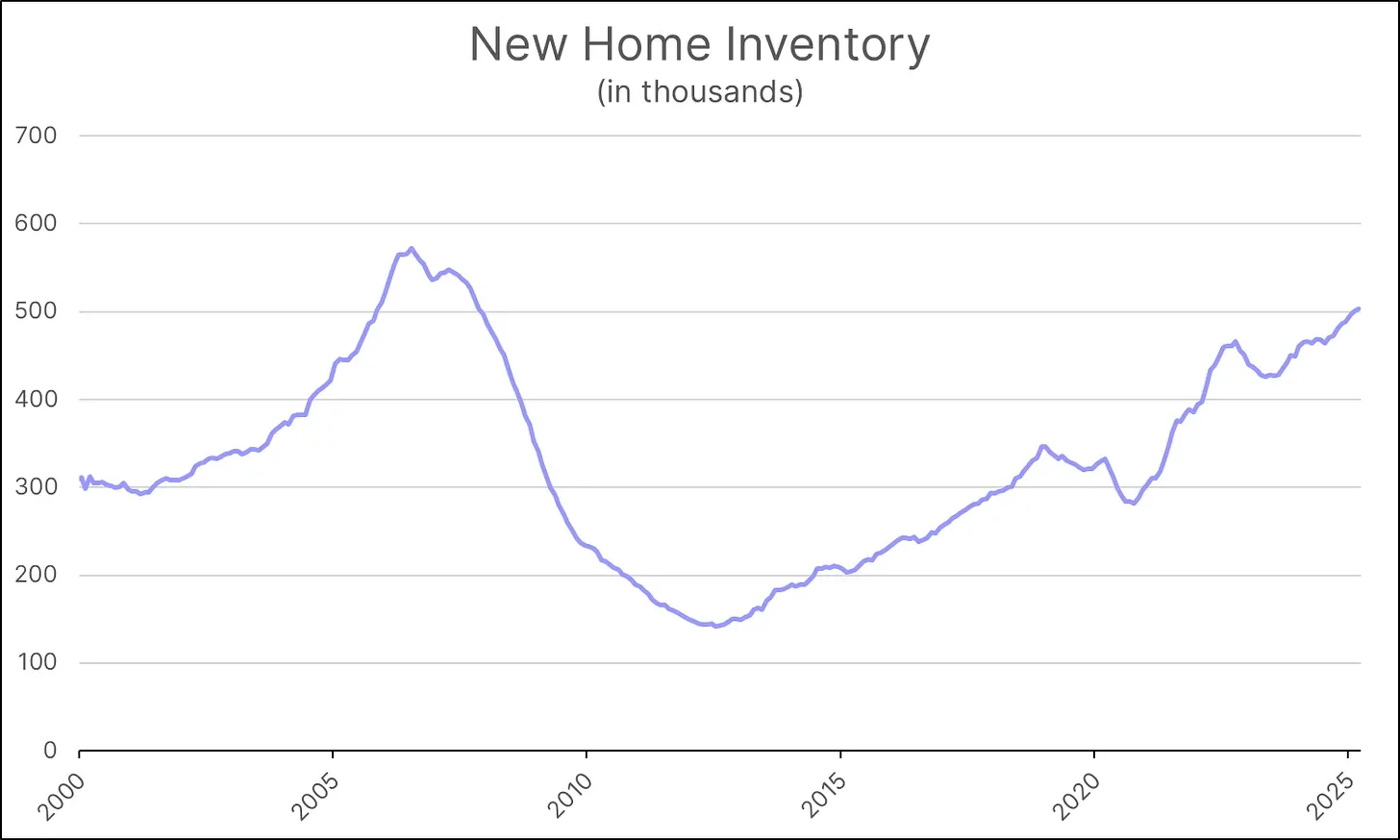

In April 2025, the U.S. Census Bureau released its latest data on the supply of new single-family homes for sale. As of March 2025, the inventory stood at 503,000 units—a level not seen since the lead-up to the Great Financial Crisis.

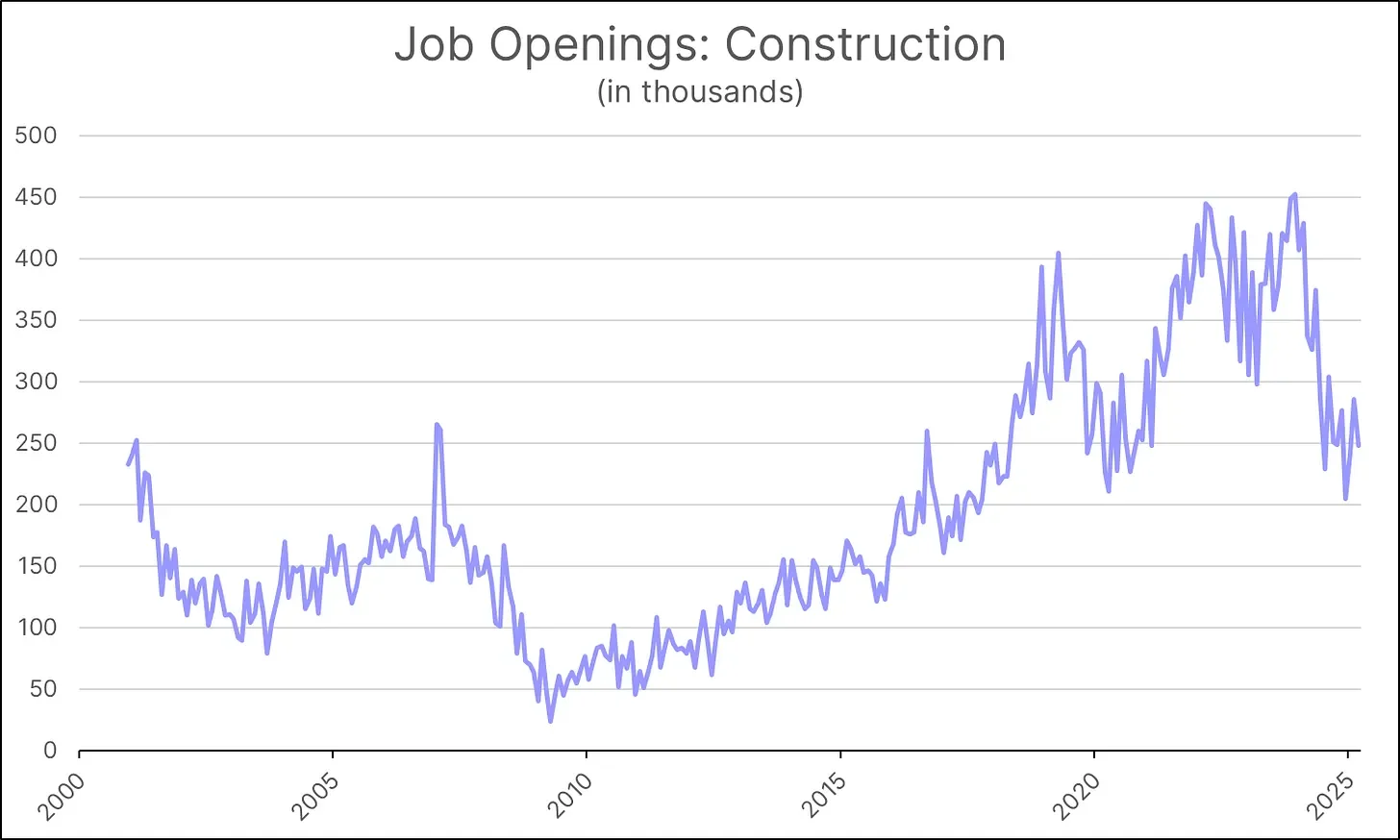

Due to the buildup in supply, construction job openings have declined sharply over the past year. However, the number of residential construction employees has slightly increased during the same period. This suggests that homebuilders have not yet resorted to layoffs, but if affordability conditions remain unchanged, we anticipate a decline in residential construction employment to occur.

Age of Homebuyer

According to the National Association of Realtors, the median age of first-time homebuyers rose to 38 in 2024, up from 35 in 2023. By comparison, during the 1980s, the typical first-time homebuyer was just 29 years old.

This shift can’t be fully understood without acknowledging that many Americans in their 20s and 30s carry student debt, which adds another barrier to homeownership. More broadly, this milestone has become increasingly out of reach as home values have not adjusted in response to the sharp rise in mortgage rates.

Higher interest rates, elevated home prices, and limited inventory in affordable price ranges, have pushed homeownership further out of reach. What was once a realistic milestone by one’s late 20s or early 30s is increasingly becoming a delayed—if not entirely unattainable—goal for many households.

Trend Reversal

There’s no universal law that says mortgage rates must continue falling, nor one that says home prices must keep rising.

And yet, that’s exactly what many people have witnessed over the past 40 years—so it became the expectation, even if it wasn’t rooted in long-term fundamentals.

Today, mortgage rates have risen, but home prices have remained elevated. One reason for this disconnect is that many homeowners don’t need to sell. For a full-fledged correction to occur, there must be a catalyst that compels homeowners to put their properties on the market.

Historically, the most common catalyst is a rise in unemployment. After all, if you lose your source of stable income, you may need to sell your home—rather than simply want to.

Unless mortgage rates decline meaningfully or wage growth accelerates significantly, the only remaining path to improved affordability is through a downward adjustment in home values.

Conclusion

Housing affordability in the United States has reached a breaking point—one that cannot be explained away by simplistic narratives about supply shortages or temporary rate hikes. Our analysis shows that, across all states, either home prices must fall dramatically or mortgage rates must return to historically low levels in order to restore affordability to its 10-year average. Yet neither scenario appears likely in the near term.

While rates have surged, prices have remained stubbornly high, largely because sellers are not being forced to transact. Without a significant economic shock—such as a rise in unemployment—or an unlikely drop in Treasury yields, the housing market will remain out of reach for many Americans.

Ultimately, the imbalance between what people earn and what homes cost must be corrected. And if income growth or interest rate relief isn’t coming, that correction will likely fall on valuations. Mispricing can persist for a time, but economic gravity always wins in the end.